Re-thinking people and nature interactions in urban Nature-Based Solutions

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, references, or to quote text.

Citation: Jones, L., Anderson, S., Læssøe, J., Banzhaf, E., Jensen, A., Tubadji, A., Hutchins, M., Yang, J., Taylor, T., Wheeler, B. W., Fletcher, D., Tenbrink, T., Wilcox-Jones, L., Iversen, S., Sang, Å., Lin, T., Xu, Y., Lu, L., Levin, G., & Zandersen, M. (2025). Re-Thinking People and Nature Interactions in Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability, 17(7), 3043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073043

Summary

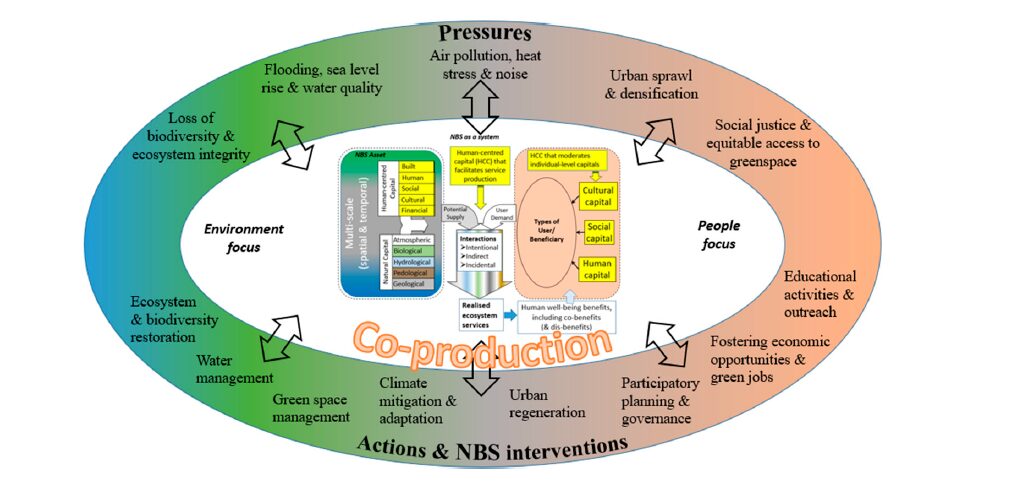

People-environment interactions within nature-based solutions (NBS) are not always understood. This has implications for communicating the benefits of NBS and for how we plan cities. The framework presented here highlights a duality in NBS. The NBS as an asset includes both natural capital and human-centred capital, including organisational structures. NBS also exist as a system within which people are able to interact. Temporal and spatial scales moderate the benefits that NBS provide, which in turn are dependent on the scale at which social processes operate. Co-production and equity are central to the interactions among people and institutions in the design, use and management of NBS, and this requires clear communication.

Introduction

In a rapidly changing world, our cities face numerous pressures that adversely affect the quality of life for urban citizens. There are technical solutions to many of these challenges, but technical solutions are often single-focus, expensive and may have unintended consequences. Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) offer more sustainable, multifunctional approaches that integrate natural systems into urban environments. However, there are still limitations to what people understand an NBS to be, and in the way NBS activities are implemented. In particular, there is frequent misunderstanding of the role of people in NBS, and a lack of understanding of how the spatial interdependencies of NBS and their surroundings help shape the functions and benefits they provide. The objective of this paper is therefore to introduce and develop a conceptualisation of NBS, which at its core represents those complex interactions between natural components and people, which are essential to providing ecosystem services.

Conceptualisation of the framework

The conceptual framework was developed through a series of discussions among a multi-disciplinary team of researchers from natural science, humanities and social science, NGOs, city and municipality officials and NBS practitioners from Europe and China. The framework was designed firstly to represent the following elements, which were identified as important in complex urban systems, and secondly to be a tool that enables transformative thinking: integration of people and nature, multi-functionality of NBS, scale, quality of NBS, co-production, incorporating pressures and drivers, governance and urban policy making, education and learning, and the role of public and private interventions to create, manage or improve NBS. The new framework proposed builds on existing environmental frameworks but overcomes their linear limitations by embedding co-production and dynamic interactions between natural and human systems.

Description of the framework

The framework has been broadened from previous framework to place the mechanisms by which ecosystem services and benefits are generated into the wider context of urban settings (see figure below). These include some of the pressures faced in urban areas, together with an understanding of where the use of NBS allows a more sustainable approach to improving the livability of cities. These actions or interventions range from ones that are more nature-focused to ones that are more people-focused. The framework separates NBS as an asset (or entity) from NBS as a system. The NBS asset comprises the bio-physical and social structures that make up an NBS, and it has the potential to provide ecosystem services to people. The NBS system comprises the myriad daily interactions of people with the asset, which result in benefits to society, as well as the higher-level governance structures that manage it.

Figure: Conceptual framework showing how NBS actions can deliver solutions in response to pressures

1. NBS as an asset

Cities are a complex mix of built and natural capital. NBS in cities contain both natural and human capital in varying amounts, which together determine their potential for use and interaction. Taking an urban park as an example, its natural capital includes geology, soil, biodiversity, water, and weather, while its human-centred capital includes built elements such as paths and benches, as well as financial, human, social, and cultural capital. This combination defines the park’s potential to provide a range of benefits to society and represents the foundation – or “what is there” from the outset.

2. Types of users/beneficiaries

The box on the right side of the figure represents beneficiaries – people who use the NBS for different purposes and have varied needs or patterns of use. Different ‘types’ of beneficiaries have different requirements that can guide how NBS are designed or managed. For example, some may be socio-economically deprived, vulnerable, or live in areas exposed to noise or air pollution. Motivations and use also vary by age and social factors, influencing how people interact with NBS and the benefits they receive. These differences shape how NBS can be designed and managed to improve access and well-being.

3. NBS as a System – Interaction Between People and Nature

The framework recognises that benefits arise only when the potential for an ecosystem service meets the demand for it among users. These “realised” benefits come solely through people’s interaction with the NBS asset. Interactions can be intentional (e.g., visiting a park to relax), indirect (e.g., trees reducing pollution or flood risk), or incidental (e.g., passing a park on the way to work). Such interactions can produce multiple co-benefits or even disbenefits depending on how people and nature connect.

4. Drivers/Pressures, Actions and Interventions

Drivers and pressures influence the NBS social-ecological system, covering key urban challenges where NBS can offer sustainable solutions. These include population growth, air and water quality, climate pressures, social inequity, and loss of biodiversity. Actions and interventions are human responses aimed at creating positive change by using NBS instead of purely technical solutions. Interventions can target the biophysical components (e.g., planting trees), the built elements (e.g., cycle paths, public spaces), or public perceptions to increase use and desirability. While pressures often act at the city scale, interventions typically occur at the neighbourhood level.

5. Wider Social and Economic Components – Governance, Business and Education

Above day-to-day interactions, higher-level governance and administrative systems influence NBS. These social and institutional structures, information flows, and interactions are forms of human-centred capital. Governance is part of social capital, while business contributes financial and human capital through innovation and partnerships. Education also plays a role by transferring knowledge and using NBS for awareness and learning. These elements operate across multiple scales, from individual assets to the wider urban system.

6. Co-production

In this framework, co-production is central to how people and institutions design and manage NBS. It is a participatory process where citizens, communities, and users are genuine participants throughout – from defining issues to implementation and evaluation. Driven by place attachment and cultural identity, co-production links people, governance, and financing to create higher-quality NBS that meet community and biodiversity needs more sustainably than technical solutions alone.

7. Quality

The quality of an NBS reflects how well its natural and human elements deliver a range of benefits. “Quality” varies depending on the ecosystem service or user needs – for example, woodland that reduces noise may not support the highest biodiversity or recreation value. Better quality means the best-fitting NBS that meets both local and wider societal and environmental needs.

8. Spatial Considerations in NBS Planning

This conceptual approach provides high-level principles to design and manage NBS more effectively while recognising the complex human–nature interactions involved. Scale matters because some NBS only deliver benefits above a certain size, while for others, quality and attributes can be just as important as area. The spatial domain of influence – or “sheds” such as air, water, biodiversity, and people sheds – defines how far NBS impacts reach. Understanding who interacts with an NBS and how helps design multi-functional spaces suited to local users and needs.

How we manage cities, now and in the future

Case study – Rhyl, UK

Rhyl is a small coastal town in Wales, population 27,000, with some pockets of severe deprivation and a level of tree-cover well below the Welsh average. The local authority (Denbighshire County Council) has instigated a programme of tree planting and wildflower meadow creation in the town. The net zero and more ecologically positive 2030 goals include increasing the tree canopy cover and species richness of council-owned and/or -managed land, whilst also creating improved spaces for the community and wellbeing. Potential locations for the planting schemes were identified based on a combination of available suitable land (existing parks with sparse tree cover, and roadside grass-verges) and areas with relatively low tree cover in residential areas. The locations were selected primarily by visual assessment on GIS or town plans, rather than a formal structured assessment of the maximum potential benefit. Some locations are in relatively wealthy neighbourhoods while others are in less affluent areas. Consultation with residents occurs before each location is improved and includes information provided by letters to residents nearby and information online. The community, including local schools, is encouraged to get involved with the tree planting and further volunteer and educational opportunities are planned at these sites after each scheme has been completed to enhance engagement.

How might we manage NBS in cities in future

Using the approaches outlined in this paper, future planning could make use of the following steps for sustainable NBS design and implementation (see figure below):

Figure: Decision steps and actions in planning and design of NBS to address urban challenges

- Assess the problem with stakeholders – Identify the main challenges, who they affect, and at what spatial scale they operate, factoring in both pressure and demand.

- Identify suitable NBS interventions – Determine the most effective type and location of intervention, considering thresholds, scale, and spatial context, and define the environment and people sheds to guide planning.

- Design through co-production – Work with stakeholders to co-design NBS that deliver primary purposes and co-benefits, ensure inclusivity, and enhance biodiversity while connecting with other NBS across the city.

- Communicate effectively – Communication underpins the process, using shared understanding and neutral framing to ensure fairness, transparency, and better outcomes for all city residents.

Conclusion

This study advances understanding of the roles of people and nature in urban settings by proposing a framework that distinguishes between NBS as entities – defined by natural and human-centred capital – and NBS as systems, encompassing people–environment interactions and governance structures. The framework highlights the importance of considering spatial domains, or “sheds,” to understand how pressures, demands, and benefits are linked. Integrating these spatial elements is essential for designing effective NBS. Drawing on economic theory can also improve communication of benefits and decision-making. Future work should test this framework in urban planning, particularly by collecting data on human-centred capital to better understand user needs, barriers, and enablers for improved NBS design and management.

Suggested citation

Jones, L., Anderson, S., Læssøe, J., Banzhaf, E., Jensen, A., Tubadji, A., Hutchins, M., Yang, J., Taylor, T., Wheeler, B. W., Fletcher, D., Tenbrink, T., Wilcox-Jones, L., Iversen, S., Sang, Å., Lin, T., Xu, Y., Lu, L., Levin, G., & Zandersen, M. (2025). Re-Thinking People and Nature Interactions in Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability, 17(7), 3043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073043

Comments

There is no content