Journal article: How to avoid the risk of maladaptation?

This article is a summary of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. It highlights some of the publication’s key messages below, but please access the downloadable resource for more comprehensive detail, full references, or to quote text.

Introduction

Climate change is increasingly affecting natural and human systems, intensifying risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, and economic growth. Adaptation is now a core element of development strategies, but adaptation measures can have unintended negative impacts, termed maladaptation, which can undermine resilience, transfer or create risks, and threaten sustainable development.

Maladaptation occurs when an adaptation measure increases vulnerability, exposure, or hazard likelihood/severity, or compromises other societal objectives. While awareness of maladaptation is growing, its conceptualization is inconsistent and operationally difficult. Practitioners face three main challenges:

- Poor conceptual clarity and lack of a universally accepted definition.

- Limited consideration of adverse effects on both targeted and non-targeted entities.

- Absence of comprehensive frameworks for early identification and prevention.

The article responds by:

- Breaking down maladaptation into actionable analytical components.

- Proposing a redefinition of the maladaptation concept that helps to operationalize it.

- Presenting a systematic and proactive approach to analyze the risk of maladaptation in adaptation measures in the early stages of adaptation planning.

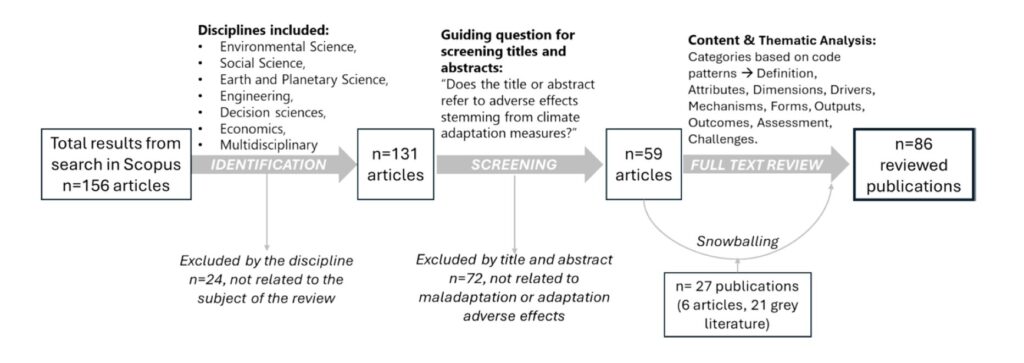

Methodology

A systematic review of peer-reviewed and grey literature was conducted, initially identifying 156 records (up to Feb 2024) using the terms “maladaptation”, “climate”, and “risk”. After refining by subject area and screening for relevance, 59 publications underwent full-text review, with 27 more added via snowball sampling (total 86).

Content analysis and thematic analysis were applied, coding material into categories: definitions, outcomes, attributes, forms, mechanisms, drivers, outputs, and dimensions. The breakdown informed both the redefinition of maladaptation and the proposed framework.

Theoretical background

Risk and climate change adaptation

In the climate context, risk emerges from the interaction of three elements: hazard (climate-related events or processes), exposure (presence of people, assets, or ecosystems in harm’s way), and vulnerability (susceptibility and capacity to cope). Risks arise not only from climate hazards but also from the trade-offs, side effects, and unintended consequences of human responses to them

Adaptation is the process of adjusting to actual or expected climate and its effects to reduce harm or take advantage of opportunities. In climate change adaptation, this means enabling social-ecological systems to anticipate, manage, and recover from climate impacts while supporting resilience, sustainable development, and well-being. The premise of adaptation is to improve current conditions, address root causes of risk, and avoid causing harm.

Defining maladaptation

Semantically, maladaptation describes actions that are counterproductive or incompatible with prevailing or future environmental conditions. In climate adaptation, it refers to measures that unintentionally increase vulnerability, exposure, or hazard likelihood/severity, or that undermine other societal goals. These outcomes can occur within the targeted system or spill over into others, creating systemic or intergenerational risks.

Multiple definitions exist—from Barnett and O’Neill’s (2010) focus on increasing vulnerability in other systems, to Magnan et al.’s (2016) emphasis on creating new drivers of vulnerability and undermining future adaptation. While related to failed adaptation (neutral risk outcome) and simulated adaptation (false sense of security), maladaptation is distinct in that it actively worsens conditions.

The lack of consensus and operational clarity on maladaptation hinders its detection and prevention. This paper’s expanded conceptualization and framework aim to address that gap, offering tools to examine maladaptation not as a binary label but as a process with identifiable causes, mechanisms, and outcomes.

Breaking down maladaptation for a more comprehensive understanding and practical application

Maladaptation involves four attributes

- It results from adaptation decisions, including inaction as an adaptation option;

- It brings negative effects in terms of risk levels or well-being;

- It can manifest within or beyond the system or both where the adaptation measures are implemented;

- It can have immediate or delayed effects, even on future generations.

Importantly, an adaptation decision should not be labelled as maladaptive if it is the least harmful course of action available. This means that an adaptation decision should not be considered maladaptive when it is the best available and reasonable option to appropriately address climate risk under the specific capacities and limitations of the implementation context at a given time, even if it slightly affects risk conditions. That also includes those cases where inaction could be considered as the most adequate response.

Forms of maladaptation

- Reinforced risk: Occurs when adaptation measures inadvertently strengthen the very vulnerabilities they aim to address, such as reinforcing dependency on climate-sensitive resources or unsustainable practices.

- Transferred risk: The risk conditions are displaced to or intensified on those connected entities that are not targeted by the adaptation measure, while the targeted entity enhances its resilience.

- Propagated risk: Maladaptation affects both targeted and non-targeted entities simultaneously, producing systemic risk increases. These effects may cascade through multiple sectors or regions.

- Induced risk: New, unrelated risks are introduced into the system as an unintended by-product of the adaptation action. It often nullifies, hinders, undermines, competes, or con- tradicts other dynamics or conditions of the system, aggravating other non-climate-related issues as well as restraining the system’s long-term sustainability.

Maladaptive mechanisms

Maladaptation can exacerbate risks (climatic or non-climatic) or trigger new ones in targeted and non-targeted entities or systems, shifting one problem to one or many other problems.

- Increasing exposure: Shifts in land use, settlement, or infrastructure placement can inadvertently place people or assets in hazard-prone areas, raising the likelihood of harm from future events.

- Increasing sensitivity (social/ecological): Measures can heighten reliance on fragile resources or exacerbate ecological fragility, making systems more susceptible to shocks or stresses.

- Decreasing adaptive capacity: Actions may erode institutional, social, or ecological resilience—reducing the ability to respond effectively to future climate or non-climate risks.

- Increasing hazard likelihood/severity: Poorly designed measures can alter environmental processes in ways that worsen hazards, such as increasing flood intensity or erosion rates.

- Introducing other risks into the system: Adaptation can trigger new hazards—both climatic and non-climatic—through unintended chain reactions, feedback loops, or the creation of new dependencies.

Drivers of maladaptation

- Contextual: These are the broader socio-economic, environmental, and governance conditions into which an intervention is introduced. Factors like political instability, deep-seated inequality, or economic volatility can limit the effectiveness of otherwise well-designed measures.

- Structural: These relate to the design and planning of the adaptation measure itself, including neglect of cross-scale impacts, trade-offs, or equity considerations. Structural flaws often embed vulnerabilities into the intervention from the start.

- Functional: These emerge during implementation, when management or operational issues—such as lack of coordination, insufficient monitoring, or resource misallocation—compromise the intervention’s intended benefits and cause maladaptive outcomes.

Outputs of maladaptation

Maladaptation produces negative economic (e.g., reduced income, increased costs), social (e.g., loss of cultural heritage, heightened inequality), and environmental (e.g., biodiversity loss, land degradation) impacts. These outcomes often develop gradually, are difficult to detect at first, and can accumulate over time, making them challenging to reverse once they manifest.

Dimensions of maladaptation

This section describes the six dimensions that shape maladaptation outcomes:

- Risk dependency: Maladaptation negatively affects the propensity to climate risks, as well as other non- climate-related risks, such as violent conflicts, political instability, environmental pollution, and species extinction.

- Well-being detriment: Negative effects extend beyond physical safety to include livelihoods, health, cultural identity, community cohesion, and other aspects of human well-being. These impacts can erode social capital, undermine development gains, and reduce the capacity of communities to respond to future challenges.

- Time: Maladaptive outcomes may emerge rapidly (e.g., immediate economic loss) or gradually over years or decades (e.g., loss of biodiversity, depletion of natural resources). The timing of impacts matters for detection and for understanding their interaction with evolving climate, socio-economic, and political conditions.

- Space: The effects of maladaptation can cross geographic boundaries, affecting areas beyond the intervention site. Impacts may spread along ecological or economic connections, influencing downstream ecosystems, neighbouring communities, or linked sectors.

- Interconnectedness: Maladaptive outcomes are shaped by, and can shape, multiple interacting processes and systems. These include development projects, political and economic trends, environmental shocks, and technological changes. Understanding these linkages helps anticipate cascading effects.

- Receptor-specific: Not all entities experience maladaptation equally. The magnitude and nature of impacts depend on each receptor’s vulnerability, adaptive capacity, and exposure, whether they are communities, ecosystems, infrastructure, or economic sectors. Some may bear disproportionate burdens due to social, economic, or geographic factors.

Re-defining maladaptation as a point of departure

The authors propose a refined definition that integrates the diverse conceptual strands from the literature while ensuring operational applicability. They define maladaptation as:

“Maladaptation is a process in which the unintended effects of an adaptation decision (including inaction) adversely alter the conditions to anticipate, withstand, manage and respond to risks (climate-related and non-climate-related) and associated impacts in one or various entities (i.e., ecosystem, economic sector, community, territory, social group, infrastructure or species) in relation to the conditions before the decision.”

This redefinition departs from narrow vulnerability-only perspectives by encompassing multiple dimensions of risk (hazard, exposure, vulnerability) and acknowledging non-climatic impacts on well-being. It treats maladaptation as a process that can emerge through direct or indirect pathways, rather than a static label assigned after impacts are visible. By embedding context sensitivity—recognizing that the “best available” option may still entail trade-offs—the definition avoids penalizing decisions made under severe constraints. This conceptual clarity lays the groundwork for a structured risk analysis that captures both intended benefits and unintended harms across systems, scales, and timeframes.

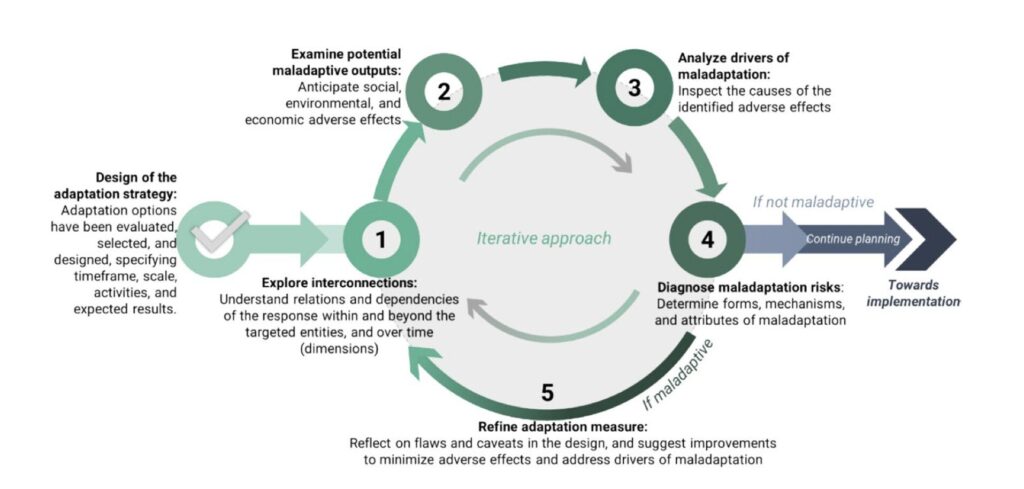

A practical framework for an ex‑ante analysis of maladaptation

To address the lack of operational tools for early maladaptation risk assessment, the authors propose a five-step framework that expands analysis beyond targeted entities to include interconnected socio-ecological systems. This broader scope captures indirect, cascading, and long-term effects that conventional approaches often overlook.

The steps are:

- Step 1. Explore interconnections – Map relationships between targeted and non-targeted entities, defining spatial and temporal boundaries to include downstream, neighbouring, or cross-sector impacts over the project’s lifecycle.

- Step 2. Examine potential maladaptive outputs – Identify possible negative social, economic, and environmental consequences, their likelihood, severity, timing, and how they might accumulate or interact with other processes.

- Step 3. Analyse drivers of maladaptation – Assess contextual, structural, and functional factors that could produce or amplify these adverse effects.

- Step 4. Diagnose maladaptation risks – Determine whether the measure meets maladaptation attributes, forms, and mechanisms; compare with alternative options, including inaction, and apply equity considerations.

- Step 5. Refine adaptation measures – Modify design to address drivers, reduce harmful mechanisms, and integrate safeguards; iterate until risks are acceptably low.

Integrated into the planning phase after option selection but before execution, the framework supports iterative refinement, leading to more robust, equitable, and sustainable adaptation outcomes.

Discussion and conclusions

The framework highlights that maladaptation is not inevitable but can be proactively avoided through early, systematic analysis and iterative refinement of measures. Incorporating equity and justice considerations is essential to ensure that benefits and risks are distributed fairly across systems and communities. The approach can also strengthen monitoring and evaluation by enabling continuous reassessment of risks under changing climatic, ecological, and socio-economic conditions.

The authors note that fully capturing the complexity of socio-ecological systems is not practical; instead, the framework prioritizes the most significant interactions and drivers. They recommend testing and refining the approach in diverse contexts, using real-world applications to improve its usability. By integrating lessons from past maladaptive outcomes into future planning, practitioners can design adaptation measures that are more robust, context-appropriate, and capable of sustaining long-term resilience.

Recommended citation

Higuera Roa, O., Walz, Y. and Nehren, U. (2025). How to avoid the risk of maladaptation? From a conceptual understanding to a systematic approach for analyzing potential adverse effects in adaptation actions. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 30:27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-025-10217-w

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.