Adaptation Finance Case Study: Craigleith Retail Park, Edinburgh

Summary

This case study, produced with Paul Watkiss Associates, explores the financing options support the retrofit of blue-green infrastructure in an urban setting. This project developed a potential business model to finance the work, reducing current and future flood risk (and to an extent, future heat risk) whilst increasing property values, footfall, biodiversity and air quality.

Introduction

Craigleith Retail Park, in northwest Edinburgh, is owned by Nuveen, and managed by Savills. A ‘partner ecosystem’ of NatureScot, Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Hydro Nation, Green Action Trust, City of Edinburgh Council, SEPA and Scottish Water have been supporting Nuveen to explore the retrofit of blue-green infrastructure at the site. This project developed a business model to finance the work, reducing current and future flood risk (and to an extent, future heat risk) whilst increasing property values, footfall, biodiversity and air quality. To do this, the project reviewed the concept design, and assessed benefits, beneficiaries, and revenue streams, as well as exploring:

- Possible funding and financing sources.

- The strategic case for the private sector to invest based on financial risk.

- Existing business model typologies that could be transferrable.

Methodology

Ecosystem services, benefits, beneficiaries and revenue streams

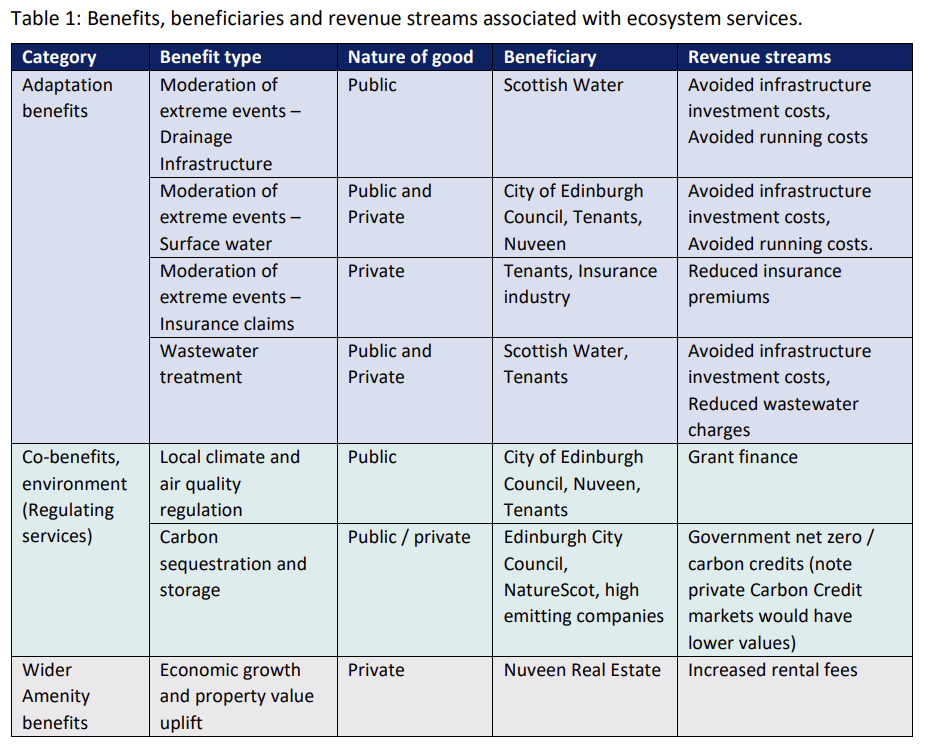

The study started with an analysis of the adaptation benefits of the project and potential revenue streams. This looked at both the economic benefits, which give the perspective of society, and the financial benefits, which give the private sector perspective. These are shown below:

The analysis of the private sector benefits found these to be modest, with the biggest benefits being the potential uplift in value of the retail park, followed by the potential savings from water entering the drainage system and thus reduced wastewater charges, though these benefits are highly uncertain. A set of wider economic benefits were considered, that included carbon benefits and ecosystem service value, along with the potential to monetise these. These were found to be lower, and in many cases, it would be difficult to realise these benefits, due to the small size of the scheme.

funding and financing sources

The analysis evaluated the deliverability, acceptability and quantum of finance arising from 31 available funding and finance sources from public and private sector perspectives. Unsurprisingly, the public sector is keen to mobilise private sector investment, whilst private sector actors tend to seek public funds to minimise or reduce investment costs given the limited short-term benefits or revenue streams. This indicates that there will need to be discussion and ‘brokering’ to get an agreed way forward on the scheme, and to agree with the relevant actors the potential for public and private blended finance.

TRANSFERRABLE BUSINESS MODELS

The study then investigated possible business models. It reviewed different business models or ways of monetising adaptation benefits, with a strong focus on generating private sector revenues. This included analysis of good practice examples for these various approaches. Each of this is unique, including a combination of partners and solutions, and as this is a nature-based solution scheme they are also specific to the local context. However, a number of promising business model typologies are beginning to emerge. Risk reduction partnerships, green densification and urban offsetting all have potential to be applied to Craigleith.

Adaptation strategies

PROPOSED BUSINESS MODEL

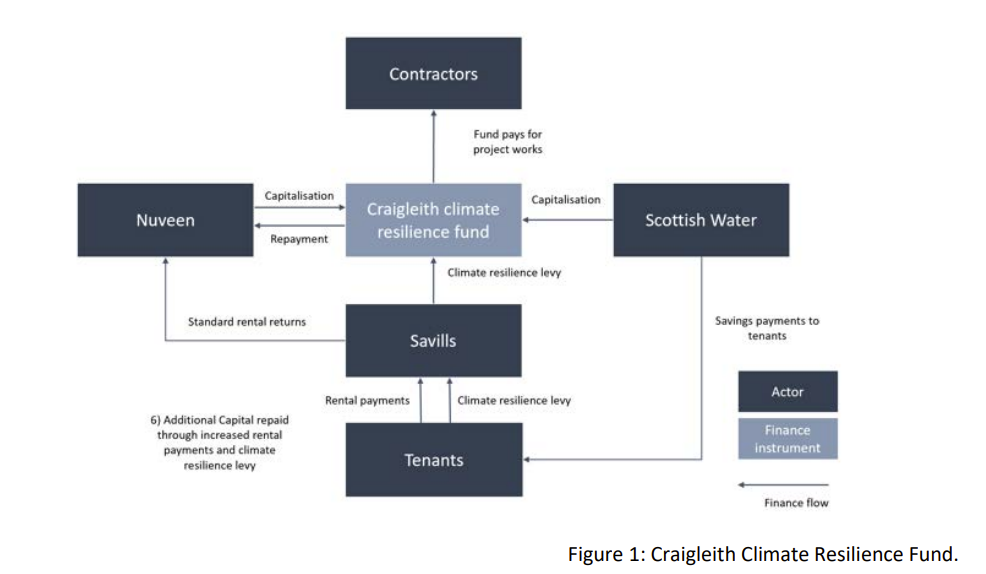

The findings were used to develop a business model and a strategic outline case for implementation. The rationale was to test if there are sufficient incentives for the private sector to invest without public sector support, and if not, the degree to which public support might be needed. Based on the analysis above, the study considers a blended finance model might work for this scheme. In the model, public and private capital is blended to invest in the scheme, with revenue streams created from higher value of the units, and reduced pressure on the drainage systems to repay the private investment. This would be managed on a day-to-day basis by Savills, in their capacity as managing agents for the site. The various partners involved in this model is shown below.

The proposed programme would have a strong strategic fit with government policy, as well as with Nuveen’s own stated objectives and aspirations as well as those of its owner, TIAA. From an economic (societal) perspective, the scheme has a low economic justification, with a benefit to cost ratio of less than 1 – i.e., the economic benefits are lower than the economic costs, when using government discount rates and a 30 year time period (note estimated BCR is 0.63:1 which indicates a small negative present value). The economic benefits predominantly arise from uplifts in property valuations and reductions in wastewater drainage. There are only very small benefits from other economic benefits streams associated with air quality and also from carbon sequestration.

From a private (financial) perspective, the scheme has to be at least revenue neutral, and potentially positive when considered over a 30 year period. This means that with gap finance from Scottish Water, the project should be able to generate sufficient revenues to pay back the investment costs. Such gap finance would also ensure a positive financial internal rate of return (IRR).

However, there are significant uncertainties around revenue generating, not least from the cost savings arising to Scottish Water and the rental value uplifts that Nuveen may be able to charge. A further analysis of benefits estimates and associated cost savings would be needed to be able to generate the final cashflow and reduce the risks with progressing the scheme. Notwithstanding these issues, there are a number of reasons for Nuveen to fund or contribute more to the investment, including management of climate-related financial risk, first mover advantage ahead of regulatory framework changes, climate taxonomies and ESG scores. There are also potential benefits from developing public sector partnership, and capacity building within Nuveen.

The analysis above has also only focused on one option, the nature-based solutions. In normal economic appraisal, projects generate a long list of potential solutions to address objectives and then shortlist these and appraise to assess their relative value for money. This project only explored one scheme and it is recommended that a light touch appraisal of other solutions, including traditional ‘grey’ adaptation investments be undertaken to allow for comparative analysis.

Depending on the climate risks and benefits, the model may have a degree of transferability and replicability across Nuveen’s wider portfolio, helping to reduce overall investment costs in adaptation through the use of a blended finance model.

Case Study Lessons

The work on the project identified several learnings, and particular challenges:

- Adaptation revenues are challenging to monetise, requiring significant effort and evidence to generate credible numbers, and many benefit streams are quite low.

- Despite being a strategic driver for large real estate companies, work under the TCFD framework has not progressed significantly enough to be a large driver for investment in adaptation options at the present time.

- Realising benefits face several barriers, including coordination and multiple actors.

- There are differing perceptions about who should pay (public or private).

- Value transfer methods for drainage savings as a result of implementing NBS are

challenging, and likely to overestimate the savings – Scottish Water’s own estimates were considerably lower over the project lifetime. - The requirements to depreciate assets on a cashflow can represent a significant challenge to positive cashflow of NBS projects where the revenue streams are relatively low.

Despite this, it is positive that a bankable solution may be possible. In many contexts, it is not possible to identify and fund bankable projects. Finally the ability to design and deliver complex projects in this manner is likely to become a more important issue as climate impacts increase, making more work on such business cases important.

Key learnings for future projects

There are a range of key learnings for future projects including:

Being clear on the range of metrics and information that are required at an earlier stage of design to be able to quantify benefits and maximise revenue streams

Business model design could be conducted in tandem with concept designs to ensure that all options for revenue streams can be explored

Schemes could consider climate change mitigation, climate risk and adaptation options together to maximise the benefits and revenue streams

Standard economic appraisal techniques encourage longlisting analysis of a number of options. Without comparator schemes, the single solution adopted here makes it challenging to provide assurance of value for money, especially given the low economic benefits and revenue generation potential

Comments

There is no content